BLOG

Diamonds in the Emerald Isle; The 5th Infantry Division in Northern Ireland

One of the common misconceptions about the US Army in Northern Ireland during the Second World War is that divisions based here were training for D-Day. In reality, from the six divisions that spent significant time here between 1942 and 1944, only the 82nd Airborne actually participated in events on 6 June. From those six divisions, two were still present and still training in Northern Ireland while D-Day took place. This is a brief account of the last of those to leave; the 5th Infantry Division.

Between late 1941 and August 1943, the 5th Infantry Division was stationed in Iceland, a posting described as both arduous and an ordeal. Planning for the invasion in Europe lead to a move to Tidworth in England ahead of a more prolonged period in Northern Ireland. Among the first personnel to arrive in Northern Ireland on 12 October was the Assistant Division Commander, Brigadier General Alan D. Warnock, accompanied by an advance party to oversee the acquisition of training areas and co-ordinate the movement of the division to their camps and billets. The division was assigned to locations around the southeast corner of County Down, establishing its headquarters at Bryansford House in Tollymore Park with their Commanding Officer, Major General S. Leroy Irwin and Chief of Staff, Colonel Paul O. Franson, eventually taking up residence there on 29 October.

First Impressions

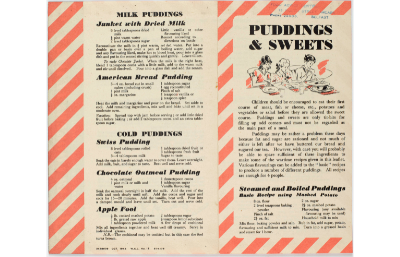

With the entire move finally completed on 10 November, the division rapidly began to make an impression locally. On 5 November, several men from the 11th Infantry Regiment were engaged in a route march when they assisted in launching the Newcastle lifeboat during low tide. The rescue attempt was to a crashed aircraft, but sadly only recovered the pilot's body. Commendations of the American's efforts were received from the RNLI depot at Borehamwood. Local church services were often attended by Americans. This was partically attributed to being stationed in towns and villages 'among a strongly religious people' and was also aided by Thanksgiving and imminent arrival of Christmas, Chaplains from the division organised twelve parties for local children, which over 3,000 attended. In January 1944, over 3,000 civilians attended military church services, and an estimated 5,452 military personnel attended civilian church services.

Training in Northern Ireland

While the division acquainted itself with its new surroundings, the first few months in Northern Ireland also saw the rapid implementation of an intensive training programme. With their time garrisoned in Iceland now firmly behind them, the activities of the 5th Infantry Division became focused on the forthcoming invasion of continental Europe.

The term training is brief, generic and often all-encompassing. At the same time, some military descriptions, such as field problems, battle indoctrination courses, and command post exercises, can seem more abstract. Fortunately, more comprehensive accounts kept by the division reveal the diverse range of training completed in Northern Ireland. Beyond the daily activities described as 'routine and appropriate to the assigned mission', one of the first locations were the division carried out specialist training was the Anti-Aircraft firing range at St John's Point on the County Down coast. Beginning on 1 December and concluding by 10 January, all united allocated men who then lived on-site for the duration of the training. Tripod and vehicle-mounted .30 and .50 calibre weapons were used, with 404 men completing the course in the first week and approximately half a million rounds of ammunition expended by its conclusion. A little over twelve miles away, a Chemical Warfare school opened within the grounds of Seaforde House. The school at Seaforde was soon graduating 42 non-commissioned officers (NCOs) per week, and by the time of its closure, a total of 33 officers and 441 NCOs had qualified. This practice of establishing a school was repeated for other specialist roles, including a signal school established just outside Newcastle, a camouflage school at Ballywillwill, and a school for Assault Detachments using Flame Throwers, Pole Charges and Bangalore Torpedoes at Dundrum. Division training was not confined to County Down, and on occasion, elements of the division travelled to locations over 80 miles away from their camps.

Due to their prolonged stay in Iceland, it was believed that the 5th Infantry Division needed more artillery firing experience. New artillery and equipment arrived, and by January 1944, the division had significantly increased its level of range firing. In March 1944, a large-scale firing exercise was held, demonstrating how artillery supported the infantry. All available troops from the division were assembled three miles northwest of Annalong, from where they viewed a target area in the mountains into which the divisions artillery began unleashing their salvos. The display was the largest of its kind held in Northern Ireland, and over 350 vehicles were used to transport personnel to the vantage point.

The Mourne Mountains were also the location where the division first became acquainted with Lieutenant General George S. Patton when he arrived to inspect personnel training in the field and to visit the division’s headquarters. Conferring with General Irwin, General Warnock, and their Chief of Staff, Colonel Franson, Patton dismissed suggestions the quality of the division had been reduced due to their two-year deployment to Iceland. After his inspection, Patton stated that the unit was ‘a very fine division’. Patton returned in March for the second of his inspection tours. Met by General Haislip from the XV Corps, his first day was spent with the 5th Infantry Division, reviewing its men on Greencastle airfield before observing a simulated attack using live ammunition and against a fortified position in the Mournes. Seemingly impressed Patton’s assessment of their capability was, ‘They will fight.

Furlough Fun

While most of the division was engaged in training at any one time, a proportion of its men were often on leave or furlough. On one occasion, it was recorded that 10% of its men were issued with 24-hour passes on a single day, which equated to over 1,400. Aside from organisations such as the American Red Cross (ARC), ensuring that personnel were engaged in appropriate leisure activities fell under the jurisdiction of the division's Special Service Section. This particular branch of the army organised entertainment, education and recreational activities on and off camp. During March 1944, 165 movies were shown throughout the division, with an overall attendance of 38,500. Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA) and the United Services Organization (USO) brought shows to six camps, while 63 dances, 26 parades and three concerts were organised. Off camp, educational tours to Portrush were available, and limited places for transportation to England, Scotland, or Wales could be arranged. In conjunction with the ARC, basketball and boxing tournaments took place, often in Belfast. The division organised a golf tournament at Royal County Down, with 130 men participating. Qualifying rounds took place over four days, split into experienced (class A) and inexperienced (class B) before the finals on 31 March. Eight of the division's best players took on a civilian team in a special finale. A few days later, all leaves furlough and overnight passes were cancelled until further notice. That order coincided with instructions received concerning a Port Overseas Movement (POM).

Preparations for Normandy

Ultimately, the restrictions were precautionary, and the POM was an elaborate embarkation exercise named JALOPY. Held over two days towards the end of April, it transported over 3,000 of the division's personnel by road and rail to Belfast docks before returning them to camp. The exercise helped refine the process of leaving camp through to embarkation. Valuable lessons were learnt and applied elsewhere for implementing large-scale movements in days rather than weeks. Other exercises were indicative of the invasion nearing. At Ballyholme, a loading demonstration involving a Landing Ship Tank (LST) and a pontoon bridge was successfully conducted. However, a repeat of the process the following day at Tyrella Beach had to be abandoned when currents began to break up the bridge. Nevertheless, the attempt did provide an opportunity to wade vehicles in deep water. A practice that the division would soon engage in at a waterproofing school on the shore of Lough Neagh.

In April a flotilla of warships earmarked for the bombardment fleet during Operation Overlord (the invasion of France) began assembling on Belfast Lough. Subsequently, men from the divisions G-3 (Training) Section liaised with naval officers onboard the USS Texas in a realistic fire control exercise. Held between 12 -14 May, several ships delivered simulated concentrations of naval gunfire on targets designated by the division’s forward observer personnel on shore. In mid- May, a detachment from the 28th Infantry Division, headed by Brigadier-General Thomas Buchanan, delivered an Amphibious Training Course. It concluded with practice operations on loading nets and mock-up landing craft. The exercise coincided with General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s arrival in Northern Ireland. His two-day tour of American units began with men from the division, assembled at Greencastle airfield. Afterwards, the general’s entourage travelled to Newcastle, Ballykinler, and Murlough, to inspect other units from the division on parade and training.

At the end of May 1944, the division numbered 14,732 men from all ranks and a comprehensive training schedule was issued running to 1 July, focusing on improving leadership, discipline and physical stamina. At the local ARC clubs, staff noticed a growing tension and on 6 June, radios in those clubs broke the news on the D-Day landings in France. The Northern Ireland edition of The Stars and Stripes had the banner headline INVASION. A growing tension was observed among the men and an increasing interest in practising French. Troops spent money more recklessly, ‘because they felt they’d soon be where they’d be unable to spend it.’ Practice shoots at firing ranges at Ballykinler, Mourne Park, and Annalong became daily occurrences, with others at Hilltown and Benbane Head. Tellingly, training in waterproofing vehicles increased, including 8 hours at Lough Neagh for each unit involved.

Departing Northern Ireland

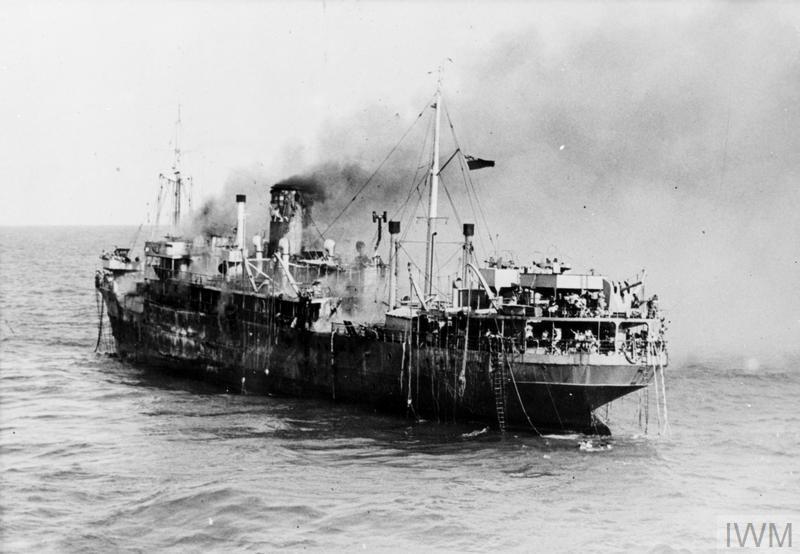

The inevitable call eventually came on 29 June, with men confined to camps and departures beginning on 4 July. Two days later, division HQ departed Tollymore Park for a ‘permanent change of station’. Boarding trains at Newcastle at 05:40 and arriving in Belfast at 06:45 before embarking on the USAT George W. Goethals. The operation was completed by 08:00. In total, 17 vessels transported the division, and the Belfast Harbour logs recorded their destination as ‘French Beachhead’. With the bulk of the division landing in France on 10 July, their eight months of pre-invasion training in Northern Ireland was now over, and the journey that would eventually take them through France, Luxembourg, Germany, Czechoslovakia and Austria was about to begin.

About the author:

Clive Moore runs the US Forces in Northern Ireland during WW2 Flickr page and is the author of the NIWM publication, The American Red Cross in Northern Ireland during the Second World War. For more information please visit the Publications tab on our website: Publications. Copies are available to purchase for £10 from the museum or via the museum's Amazon account. Clive is presently researching material for a book on the US Army in Northern Ireland.