Blog

Nobody Died in the Blitz

Over four nights in April 1941, Belfast lived through the unimaginable horror of the Blitz. Descriptions of the second bombing raid, in particular, conjure the most nightmarish images. It began with a low rumble, which became a roar, when, suddenly, the whole city was bathed in a gorgeous and deadly light, as the Luftwaffe's phosphorescent flares burst in the air. Then the bombs started to fall.

By the end of the four raids, 55,000 houses were destroyed, the city's industrial heartland was flattened, and 950 people were killed, with thousands more maimed and wounded.

But nobody died in the Blitz. At least not in the paintings and drawings that were produced in Belfast in the aftermath of those raids.

This blog will examine how three Belfast artists represented the Blitz in their work: William Conor, Arthur Armstrong and Max Maccabe. It will put their portrayals in the wider context of the 'War Art' genre and ask questions about the taboos and self-censorship that are necessarily involved when painting such devastating acts of violence against the human body.

One of the surprising chroniclers of the Blitz was the stalwart reactionary artist, William Conor. Conor's images of life in Belfast through the 1920s and 1930s were reassuringly unthreatening. He left us stacks of pictures of laughing shawlies, stoic dock workers and stone-faced businessmen. Although the city was rocked by economic and political convulsions, Conor's portraits of even the most destitute men and women radiate a sense of contentment and stability.

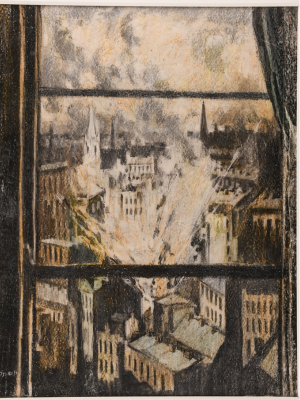

When the bombs fell, it is therefore surprising that this most mannered of artists produced an unnervingly thrilling image of war.

Conor captures the way in which, even in the dead of night, an entire street could be illuminated by a single bomb blast. The surrounding houses remain in the shadows, creating a sense of theatricality in this brightly lit group of buildings. He purposefully elongates the windows so that they resemble rows of shrieking mouths. What’s most tantalising is that you get a real sense of the adrenaline rushing through his body, of the perverse excitement that he felt.

Conor’s depiction of the explosion itself borders on the exhilarating. He captures the milliseconds after the initial blast, just as the flame and brick burst up into the air. The simple, powerful lines he created with his crayons are almost joyful. It’s like a work by a postwar abstract artist has been dropped into the middle of a traditional Victorian cityscape.

The destruction of so much of Belfast’s Edwardian splendour was profoundly traumatising. But it also proved to be a surprising impetus for creation. Men who had barely painted in their lives went out into the ruins to commit the destruction of their city to canvas. Artists like Gerard Dillon, Daniel O’Neill and George Campbell found the decimated buildings to be fertile ground for their artistic talents. They would go on to form the knot of highly influential Neo-Romantic artists known as ‘The Group’ or the ‘Belfast Boys’.

Although Dillon, O’Neill and Campbell were seen as Belfast’s most significant talents of the postwar generation, it was another member of The Group, Arthur Armstrong, who produced an image of the Blitz that retains a sickening resonance today.

This picture is, as far we know, the first thing ever painted by Armstrong. Before the war he had been a student of political science and architecture. But the incomprehensible scale of the Blitz’s violence ignited a need to take up a brush and commit these scenes to canvas.

Armstrong’s houses are like no houses in Belfast. They tower over the two tiny figures on the street and have only a few windows dotted around their blank facades. The buildings resemble huge crags that loom so far up they block out the sky. This hugeness recalls Edmund Burke’s essay on the sublime and his ideas on astonishment:

'The passion caused by the great and sublime in nature... is astonishment; and astonishment is that state of the soul, in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror. In this case the mind is so entirely filled with its object, that it cannot entertain any other, nor by consequence reason on that object which employs it.'

Burke may have been writing about the astonishment felt at witnessing the awe-inspiring forms in nature. But, at this moment in history, the scale of the destruction of Belfast could only be compared to a natural disaster. This sort of persistent aerial bombing of a civilian target had never before been witnessed. The overwhelming power of the Blitz - the combination of fire, deafening sound and toppling brick - could only be compared to volcanic eruptions, firestorms and earthquakes. The fact that the people of Belfast were convinced that the Luftwaffe could never reach the city, and were therefore entirely unprepared, only heightened this sense of bewilderment.

Astonishment and bewilderment were, doubtless, the only appropriate emotional response to the bombings. Burke’s association of terror with astonishment goes a long way in explaining the psychological state of Armstrong and his fellow Blitz artists. The idea that the mind is so overcome by an image of horror, that it cannot focus on any other image, is particularly striking when considering the way in which Armstrong fills the entire canvas with these desolate houses. Nothing else existed for Armstrong at the moment he painted this except for his shattered city. The distorted scale of these giant houses is not realistic. Instead, it is a depiction of his all-encompassing sense of shock at what he has lived through.

Armstrong shows us that, in the face of such destruction, humans lose their reason; they become dwarfed and isolated beings who can only pass each other in silence. Unlike Conor, Armstrong did not paint the physical reality as he saw it. Instead, he left us with an emotional testimony of what it felt like to be made so small and anonymous as a witness to world of historic violence.

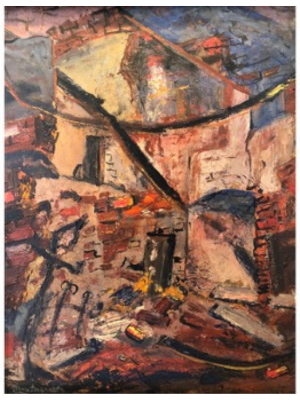

Max Maccabe came from the same generation of artists as Arthur Armstrong. He turned 24 in 1941 and, although he had attended the Belfast School of Art, had not yet settled on a style of painting. This youthful inexperience meant that Maccabe was able to respond in an equally free and untraditional style as Armstrong.

More than any other artist, he matches a feel for his material with his personal response to the bombings. His paint is applied with thick and uneven blotches, giving us an insight into the psychological pain he suffered as he saw his familiar surroundings collapse into rubble. Reds and oranges creep across the brickwork to create a hellish atmosphere. Familiar objects become strange and threatening. Inexplicable lines of black scythe across the canvas.

If it weren’t for the lamppost on the left of the painting it would be hard to orientate yourself in this space. Are we inside a house that has collapsed? Perhaps in the back alley of a terrace. What looks like a small sliver of sky at the top of the painting has the outline of bricks in it. The distinction between interior and exterior has been completely obliterated. No matter where you turn you are met with more hot brick, more fire, more smouldering rafters.

Maccabe is so effective at capturing the horror because he zooms in on a single house. Unlike Armstrong and Conor, there are no extraneous details. He concentrates our minds on the overheated, claustrophobic nightmare of his surroundings. The small number of Blitz paintings that he produced are a high point in his artistic career, and put one in mind of the war paintings of Renato Guttuso.

But something is missing from these images. This essay starts the way most essays on the Belfast Blitz do: ‘55,000 houses were destroyed, industrial heartland flattened etc.’ That list ends with 950 people dead. It is notable that there are no dead, maimed or wounded in these paintings. Arthur Armstrong shows some of the survivors, but all they do is move hopelessly through a devastated architecture. These artists appear more concerned with the fate of houses than with their fellow citizens.

To understand this lack of bodies we have to go back to the end of another war.

In the aftermath of the First World War, the Anglo-Irish society artist, William Orpen, was commissioned by the War Office to paint the Tomb of the Forgotten Solider. With its long, dark corridor and total stillness, Orpen’s painting is both stately and ominous. But this work’s eerie quality cannot be explained by what is visible, for it has multiple buried bodies.

In his original rendering, Orpen painted a pair of half-naked, bedraggled soldiers guarding the tomb. Their decaying bodies and mournful, silent wails were meant to act as a confrontation with the viewer. ‘This is what the “Great War” actually looked like’ they seem to say. ‘There is no glory at the end of war. Only corpses. And no amount of flag waving and fine architecture can conceal that.’ But the War Office demanded that Orpen paint over his corpse-guards. The officials who sent so many men to die could not face the carnage, even when painted in such a safe manner.

Death can only be suggested: to show the actual damage done to our fellow humans in a painting is perverse and unacceptable.

Orpen’s case is so interesting because it suggests that, even in the era of mass-produced war photography - of prone bodies lying in the mud of the Western Front, of piles of dead casually flung onto the back of lorries - there remains an unspoken taboo around what painters and draftsmen can show. There are some things that can only be written down or photographed, but never committed to canvas. What a painting hides, therefore, is just as important as what it reveals.

In 1941 an ARP man named Jimmy Doherty recorded some of the most powerful descriptions of the Belfast Blitz. He wrote of people being ‘blown to pieces’ and how, during one hastily arranged funeral, ‘blood was seeping out of the coffin’. His most disturbing memory was trying to dig through the rubble of a collapsed house:

'We tackled the pile of masonry with iron bars. We pulled at it... with our bare hands and gently moved the beams aside. A passing auxiliary fire service team with a trailer pump sprayed the hot bricks to cool them... When we eventually came across some bodies, they had been cooked under the hot bricks... Even as I write, I find it difficult to describe the full ghastliness...'

Like these three painters, Doherty was recording a lived experience. But the images he conjures can exist only as words on a page. This license to depict such violence in writing extends to the realms of fiction: Brian Moore’s novel ‘The Emperor of Ice Cream’ and Lucy Caldwell’s ‘These Days’ contain similarly horrendous descriptions of carnage. But to paint any one of these authors’ images onto a canvas would be considered obscene. Reading Doherty’s account, one can’t help but revisit the glowing bricks of Max Maccabe’s painting or the gigantic ruined houses of Arthur Armstrong and wonder what they saw and what they aren’t showing us.

But perhaps the ruined architecture in these three works does more work for us than we recognise. Can we see the bombed-out houses as stand-ins for real human bodies? Do they provide us with a way of acknowledging what happened to real people’s flesh and bones? Are we meant to recognise that buried within Armstrong’s houses, there are charred corpses and severed limbs? Do Max Maccabe’s glowing bricks suggest to us the horror of what was underneath? Do the bodies ever really leave us?

In the language of psychoanalysis, the idea of ‘transference’ is particularly useful here. The redirection of feelings, desires and pain onto another person or object, and away from the original source of those emotions, explains so much of what was happening in art at this time.

One of the most potent artistic iterations of this psychic move is to be found in the world of photography. The Jewish German photographer, Madame d’Ora, created a series of abattoir pictures, which are perhaps some of the most disturbing works of the postwar era. Rows of severed calves’ heads and legs loom out of the frame. Meat hooks, chains and streaks of blood cut across one’s consciousness in ever-more unsettling images. But we all know that what d’Ora was really photographing was the horrors of the Holocaust. Yet, to show that kind of degradation being visited on a human body would be too painful to experience. A simulacrum had to be found. For Conor, Armstrong and Maccabe the ruined houses of Belfast act as equally potent objects onto which they could project all the pain and trauma of witnessing the pulverisation of fellow human beings.

These artists did not retreat from painting the devastation of the Blitz. Nor were they subject to any form of official censorship. Instead, they found a necessarily sanitised visual language which could describe the horrors they witnessed, while maintaining a sense of security and decorum.

All images are mediated through our own experiences and imaginations. And so, it is left to us, the viewer, to read human bodies back into the houses that each artist painted.

The Northern Irish sculptor, Carolyn Mulholland, recognised this when she created her supremely insightful Blitz memorial for the NIWM in 2008. Her work acknowledges the simultaneous presence and absence of human bodies when it comes to representing this terrible chapter in Belfast’s history. However, this sculpture also suggests that, with the distance of time, the bodies are beginning to rise up to meet us. The ghostly figures that have been buried so long have begun to take solid form and ask us to confront the physical violations they suffered in the bombings. It is a powerful artistic statement that we should recognise the actual violence of the Blitz, and that we should not accept the works of Maccabe, Armstrong and Conor at face value. Mulholland demands that we move beyond the symbolic and metaphorical language of the past, that we overcome the taboo of representing atrocities and come face to face with the real human tragedy of those four devastating nights in 1941.

Special thanks to the Imperial War Museum, London and Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg for their kind contribution of images to this essay.

About the Author

Matthew Maw was born in Belfast and studied literature at Royal Holloway, University of London (BA) and New York University (MA). He is a freelance exhibition coordinator and writer. His most recent piece of writing was a contribution to the San Francisco exhibition of the Northern Irish artist, James Kennedy. Since 2022, Matthew has worked with NYU, the Ulster Museum, Down County Museum, the Leo Baeck Institute, and the Lyric Theatre to deliver exhibitions of work by significant Northern Irish artists. Matthew write regularly for 'Belfast's Lost Modernists', an Instagram page which aims to introduce the city's postwar art scene to a new audience.

Further Reading

- Barton, Brian, The Belfast Blitz, Ulster Historical Foundation, 2015

- Burke, Edmund, A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, Penguin Books, 2004

- Caldwell, Claire, These Days, Faber and Faber, 2020

- Huberman, Didi, Confronting Images, Pennsylvania State University, 2005

- Karmel, Pepe, Abstract Art: A Global History, Thames and Hudson Ltd, 2020

- Moore, Brian, The Emperor of Ice Cream, Viking Press, 1977

- Sontag, Susan, Regarding the Pain of Others, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003

- Woodward, Guy, Culture, Northern Ireland and the Second World War, Oxford University Press, 2015