Given the introduction of conscription in Great Britain in 1939, it is clear that tens of thousands of queer men and women ended up in uniform despite same-sex activity, at least in the case of the former, being illegal. With a constant demand for manpower in the armed forces, there is certainly evidence that the authorities were willing to turn a blind eye to a recruit’s sexuality at the required initial medical examination, even when it was manifestly obvious.

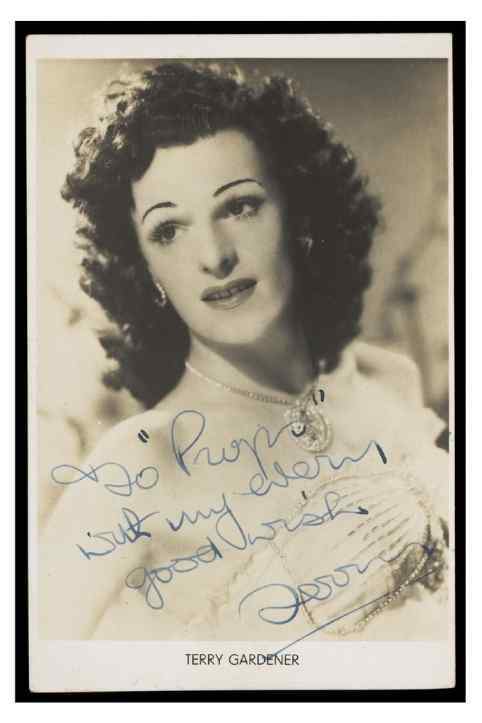

For example, Terry Gardener, who worked as a drag queen before the war and wanted to continue in show business, was advised by his friends to really camp it up and be outrageous in front of the medical board to ensure he would be rejected. Unfortunately for Gardener, despite his best attempts, he was passed and sent into the Royal Navy as a cook. Indeed, it seems that in the event that a recruit’s queerness was identified by a medical board they were more likely than not to be accepted anyway because of a widespread belief that they could be straightened out by the rigours of military life.

Some of the richest sources of information we have for the experience of queer men and women during the war are the oral history interviews conducted with Second World War veterans later in life. They make clear that there were plenty of opportunities for service personnel to explore same-sex desire, particularly in the context of an environment which encouraged physical intimacy and close personal relationships with one’s fellow men or women. As one RAF veteran recalled sixty years later: ‘Let’s face it. You’re queer and you’re surrounded by men. I was living in a man’s world and I was queer and you can’t ask for much more than that.’ Similarly, Sarah Allen, interviewed in 1990, described the outbreak of war as a ‘Godsend’ because it meant she could escape home and a succession of uninteresting boyfriends by joining the ATS where she encountered queer women for the first time and had her first physical same-sex relationship.

Of course, we should not make any assumptions about an individual serviceman or woman’s sexuality, particularly as there is evidence that – at least in the case of men – the need for sexual relief coupled with fear of catching a venereal disease from a visit to a brothel meant that otherwise heterosexual servicemen would quite happily use their queer comrades to satisfy their needs. For example, in a 1998 BBC Timewatch documentary queer naval veteran Dennis Prattley talked about his pride in fulfilling an emotional function for many men onboard his ship. He said he ‘made a lot of boys happy’ and that he did his bit for his country, with one of his crewmates telling him that he reminded him ‘of my girl back home.’ Fellow naval veteran John Beardmore also recalled the ‘wingers and oppos’ system in the Royal Navy where ‘wingers’ were senior men assigned to mentor new recruits and ‘oppos’ were seamen of a similar age and rank who were expected to guide them. According to Beardmore, there could also be a sexual element to this relationship: ‘I know of fellows who were oppos and who were having affairs at the time who went on to become godfathers to each other’s children.’

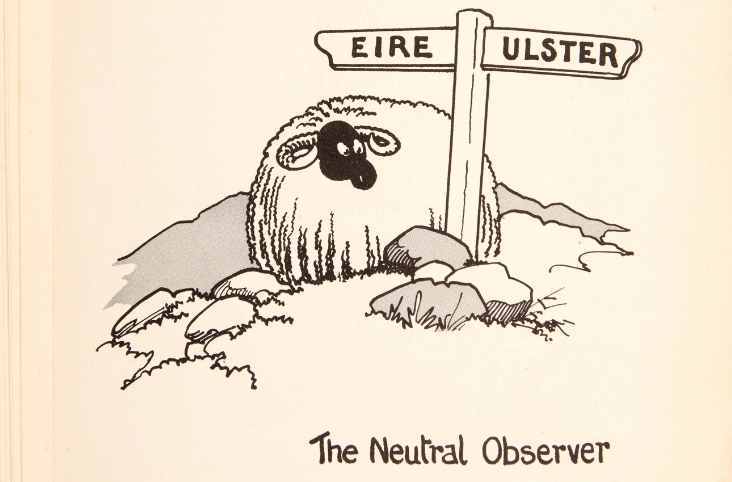

There also seems to have been plenty of same-sex activity in the women’s branches of the armed forces. Elizabeth Reid Simpson, interviewed in 1998 for the Imperial War Museum’s oral history collection, remembered serving alongside quite a few lesbians in the WAAF including one occasion while she was stationed in Northern Ireland, probably at RAF Ballyhalbert in County Down. Simpson came across a female couple at the station who slept there together and after complaining one night about the noise coming from where they were meant to be on night duty, she was told by another woman: ‘Where were you brought up? Don’t you know anything? They’re lesbians and they always manage to get posted together…they don’t fancy you so get back to bed and go to sleep and don’t bother about them.’ Her memory was that her fellow servicewomen simply ignored this lesbian relationship.

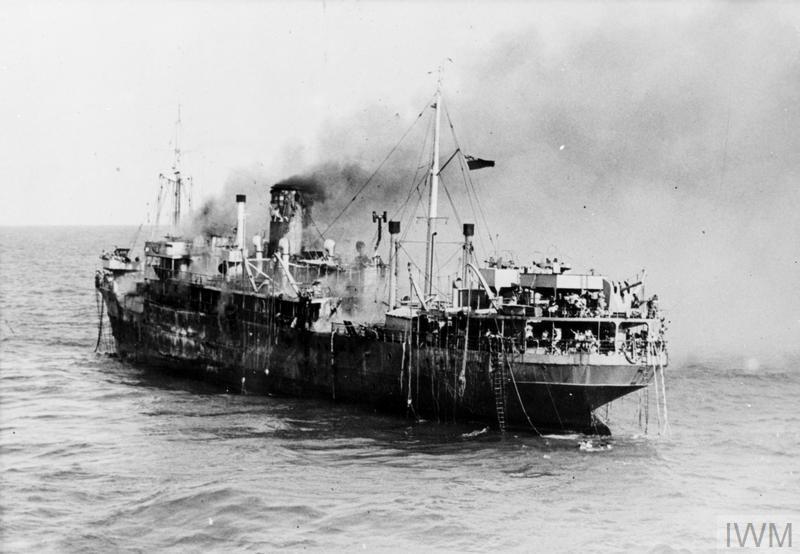

One other common element of the experience of queerness in the armed forces was the role many queer men played in keeping up morale, particularly while on campaign. Terry Gardener, the drag queen turned Royal Navy cook, regularly entertained his crewmates by camping it up during the war: ‘Everyone likes to laugh whatever the circumstances, and believe me there were some dreadful, dreadful circumstances especially on the Western approaches.’ John Beardmore also recalled a coder called Freddy on his ship who had been a chorus boy during peacetime and who used to relay messages to the forward guns from his commanding officer with the order: ‘Open fire, dear.’ According to Beardmore, Freddy was immensely popular with the crew and also enjoyed impersonating Vera Lynn and Gracie Fields whenever the stress of battle became too much for everyone. As one army veteran later described his queer comrades camping it up during the Normandy landings: ‘They had this amazing capacity to see the ridiculous part of life. I think they felt they’d got to be brave in front of the straight lot.’

Of course, the home front also saw its fair share of queer experiences, both for those in and out of uniform. In London, where there was already a well-established public and social queer network by this period, queer men like the writer and actor Quentin Crisp enjoyed the sexual opportunities provided by the Blackout; as he described living in wartime London in his autobiography The Naked Civil Servant: ‘The city became like a paved double bed.’ Crisp also welcomed the arrival of American troops in 1942, commenting that ‘they flowed through the streets of London like cream on strawberries, like melted butter on peas…Never in the history of sex was so much offered to so many by so few.’

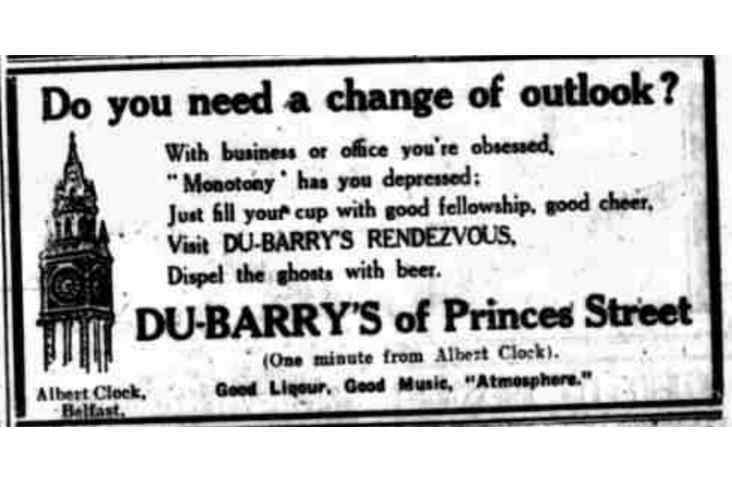

What was true of London was also true, albeit on a smaller scale, in other places in the UK like Blackpool, Liverpool, Manchester, Glasgow and, of course, Belfast. In Northern Ireland’s capital city, Du-Barry’s near the Albert Clock was a well-known queer venue both during and for many years after the war; indeed, the area around the docks seems to have been something of a cruising ground for men looking for sex with men, with at least one soldier and a male civilian being caught having sex at Queen’s Quay in 1941. And while there appear to have been relatively few courts martial of servicemen for the offence of ‘indecency’ during the war (some 1,800 out of 5.9 million men who served in the UK armed forces between 1939 and 1945), certainly in Northern Ireland there were several civilian court cases involving servicemen on trial for same-sex activity.

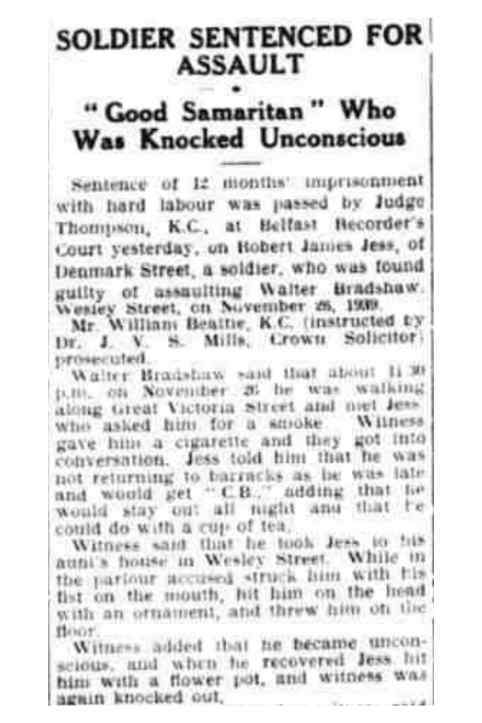

For example, in January 1940 soldier Robert James Jess was found guilty of assaulting civilian Walter Bradshaw after a late night encounter in a house in Wesley Street in Belfast the previous November which resulted in a prison sentence of twelve months with hard labour; what the local newspaper reports failed to mention is the fact that Jess was charged with ‘assault with intent to commit buggery’, something that historian Tom Hulme has confirmed from examining the original police file in the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland.

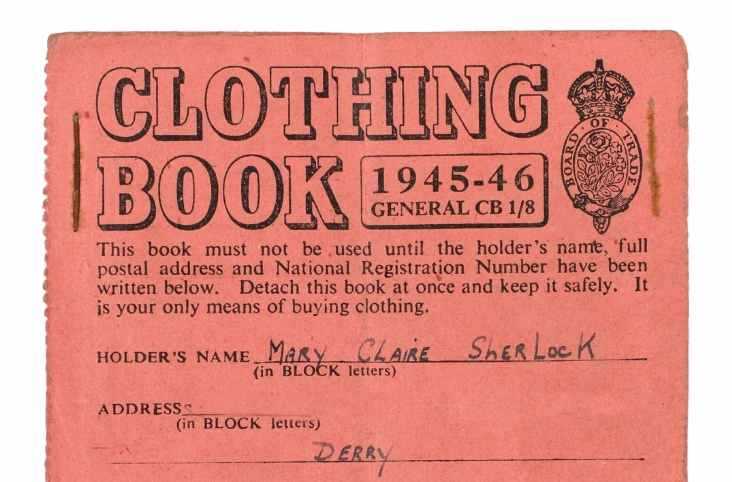

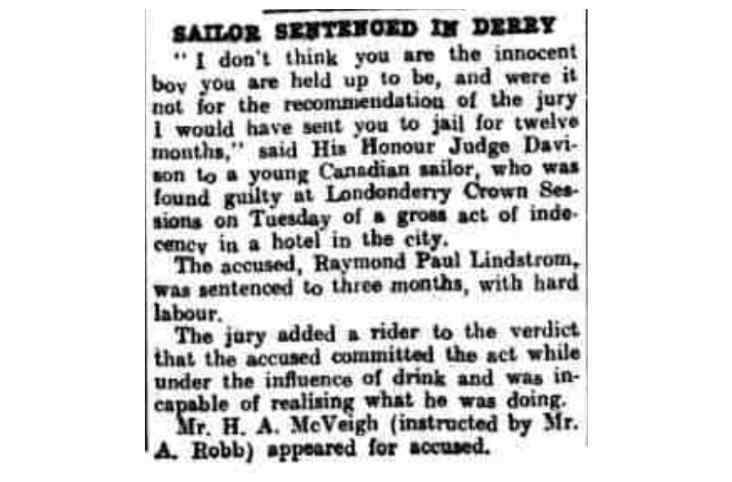

And in June 1944, a Royal Canadian Navy sailor, Raymond Lindstrom, was convicted of gross indecency and sentenced to three months’ imprisonment with hard labour after a drink-fuelled encounter with a US Army officer and another Canadian sailor in a Londonderry hotel room. It seems the case would not have come to the authorities’ notice other than that both sailors were originally charged with robbing the American officer, a charge subsequently dropped, and one can only speculate on how many similar sexual encounters must have taken place in hotel rooms, private houses, streets, parks, barrack rooms and other places where queer people were brought together during the war.

Certainly as far as queer men were concerned, historian Matt Houlbrook has described the Second World War as ‘a kind of sexual utopia, containing freedoms and possibilities absent both before and after.’ This is especially true given that in the post-war period there was something of a backlash against queer men, something that has been attributed to factors including calls to return to ‘traditional’ moral standards and concerns over rising divorce rates and the declining national birth rate. Given the increased persecution of queer men in the 1950s, is not surprising to learn then that in 1938, 719 men were convicted of same-sex activity in England and Wales but this number then went up to 2,109 in 1952. As Quentin Crisp later put it: ‘The horrors of peace were many.’

Interviewed in the late 1970s about his wartime experiences, one queer veteran called Roy recalled his service in the Royal Army Medical Corps: ‘It was such a lovely war. Oh what went on was nobody’s business.’ While it is clear that the Second World War was not a universally ‘lovely war’ for queer people, what is also evident is that the war opened up all kinds of new experiences for queer men and women, both in and out of uniform. To that extent, historian Emma Vickers is right to note that ‘In the widest of senses, the war represents an exceptionally important juncture in the history of queer Britain.’

About the author:

Michael Fryer works as the Outreach Officer at the Northern Ireland War Memorial.

My thanks to Dr Tom Hulme and Dr Richard O’Leary of the School of History, Anthropology, Philosophy and Politics at Queen’s University Belfast, Jeff Dudgeon and Doug Sobey for their help in researching this topic.

Further Reading:

Stephen Bourne, Fighting Proud: The Untold Story of the Gay Men who Served in Two World Wars (I.B. Tauris, 2017)

Matt Houlbrook, Queer London: Perils and Pleasures in the Sexual Metropolis, 1918-1957 (University of Chicago Press, 2005)

Alkarim Jivani, It’s Not Unusual: A History of Lesbian and Gay Britain in the Twentieth Century (Michael O’Mara, 1997)

Kevin Porter and Jeffrey Weeks (eds.), Between the Acts: Lives of Homosexual Men 1885-1967 (Routledge, 1991)

Emma Vickers, Queen and Country: Same-Sex Desire in the British Armed Forces, 1939-45 (Manchester University Press, 2013)