During the Second World War, RAF marine tenders were supplied to the McGarry organization at Ardmore to facilitate their contracted responsibility for maintaining targets and salvaging aircraft which crashed into the lough.

Twelve flying-boat moorings were established at Sandy Bay, in the shelter of Ram's Island, along with a number of marine craft moorings for attendant vessels and refuellers. Gas-lit navigation buoys were also laid out to guide incoming and outgoing aircraft, mainly Short Sunderlands, Consolidated Catalinas and Consolidated Coronados. In addition, RAF marine craft operated from Antrim and Sandy Bay, complementing the work of the McGarrys.

The first flying boat to land on Lough Erne was in February 1941. Soon more modern types followed, especially, the slow but utterly practical Consolidated Catalina and the magnificent Short Sunderland. These included Nos. 201, 202 and 240 Squadrons RAF and Nos. 422 and 423 of the Royal Canadian Air Force. For the most part operational boats were based there, while training was carried out by 131 Operational Training Unit (OTU) at nearby Killadeas. From 1942 Lough Erne was also used by BOAC as a back-up facility to the transatlantic flying-boat terminal at Foynes on the Shannon estuary. The Marine Craft Units stationed on Lough Neagh and Lough Erne included: seaplane tenders, firefloats, refuellers, bomb scows, servicing and crew tenders.

Lough Erne was, perhaps, a little spartan,

‘Daily checks of the boats were done at the moorings. In bad weather with high winds and high waves, it was a tricky business getting out to the flying boats. There was always a good selection of launches and pinnaces to take the maintenance crews out to the boats. When they wanted to come in again, it was simply a matter of flashing ‘D’ on an Aldis lamp, and a launch would appear.’

January 1945 was the low point as John Lloyd-Williams of the Marine Craft Section recalled, ‘Lough Erne was frozen over and the ice was up to eight inches thick in shallow water. Loaded refuellers patrolled the moorings every few hours to make sure they were kept clear of ice. We were like explorers in the Arctic slowly going round in the moonlight breaking the ice.’

Air Sea Rescue in Northern Ireland

By 1943, RAF Air Sea Rescue Units in Northern Ireland were as follows: No. 56 Portaferry, at the mouth of Strangford Lough, No. 57 Donaghadee, on the seaward side of the Ards Peninsula, No. 58 Larne, covering the North Channel and No. 60 Culmore, on Lough Foyle. They were equipped with 67 ft Thornycroft High-Speed Launches (HSLs) and 60 ft ASR Pinnaces. For administrative purposes they had parent RAF stations, Ballykelly for Culmore, Aldergrove for Larne, and Ballyhalbert for Portaferry and Donaghadee. There was also a unit at Portrush parented by RAF Limavady.

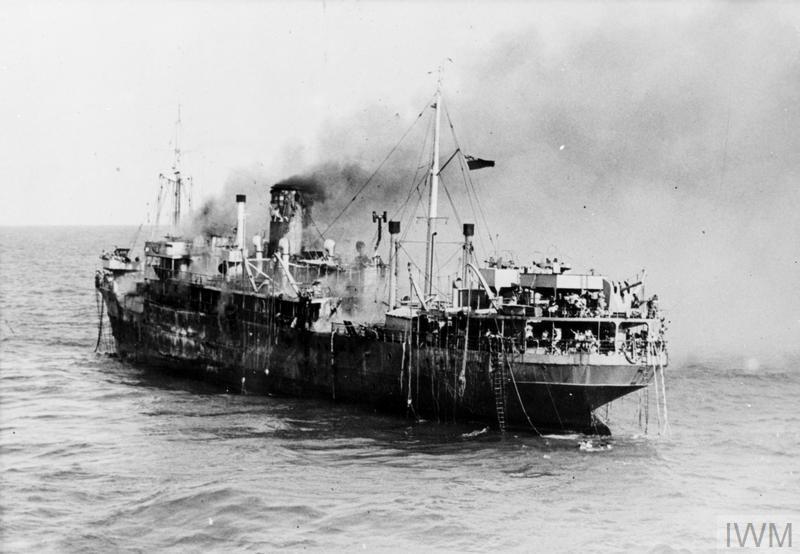

The two main ASR craft were: the 67ft Thornycroft was the first of the third generation RAF HSLs and designed from the outset for rescue work. It had better accommodation for the crew, the sick bay was larger and therefore better able to receive more rescued aircrew in greater comfort. Speed was sacrificed for greater range and the physical strain lessened for crew as a consequence. It was particularly appreciated for its larger and well-equipped galley, containing an impressive array of storage racks for crockery, a good size sink and a pressure paraffin oven. Thermos containers of hot soup and tea etc were always ready to hand. The radio room was for two operators; W/T, RD/F and IFF were standard equipment with VHF installed later. The bridge was a new and important feature which enabled the officer in command to have a much-improved view and so greatly aid the early sighting of an object floating in the sea. Defensive armament was provided by three turrets, each mounting twin 0.303 Brownings, one turret on each side of the bridge and the third aft. The aft turret on some of these craft was omitted, being replaced by a 20mm Oerlikon cannon mounting. Early models were powered by two Thornycroft RY/12 650hp petrol engines, which were followed by the installation of three Napier Sea Lion 500hp engines. Maximum speed was in the region of 24-26 kts. The ASR Pinnaces were 10 kts slower, with three Perkins 56M 130hp diesel engines and less well armed, normally being fitted with two enclosed turrets, each housing a single .303 Vickers.

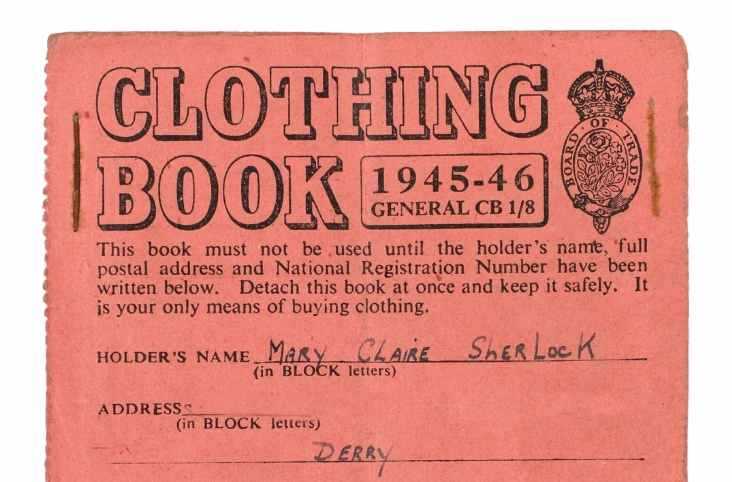

A former member of No. 56 ASR Unit, Corporal Ken Sargent, recalled, ‘Portaferry was one of the better postings, particularly as it had a very good cook, who had worked for P&O. A favourite delicacy was crabs, which were obtained from local fishing boats in exchange for RAF supplies.’ HSL No. 2609 was based there, Flying Officers Smith and Cook were the two officers. The unit was situated at 3 Castle Street, an upstairs room of which was converted to house a stage, with a bank of spotlights and a small, thatched bar, with paintings of Hawaiian ‘hula girls’ on the walls, providing entertainment facilities for unit members and invited local residents.

A variety of craft were based in Portrush: an Armoured Target Boat, a Seaplane Tender, a General Service Pinnace, a Special Duties Pinnace and a couple of dinghies. They probably carried out range safety for the Portrush Air Gunnery and Bombing Range. There was also a Royal Naval Battery Gunnery Range at Islandmagee which trained Merchant Naval gunners for armed merchant ships and was adjacent to Larne.

The Reason Why

It may be wondered why there were seven centres of RAF marine craft activity in Northern Ireland, over and beyond the requirements of the flying boats of Coastal Command in the two inland loughs. The geographical position of the country is one answer, with aircraft having to either cross the Atlantic Ocean from the USA and Canada or the Irish Sea/North Channel. But why was there so much aerial traffic? There were 25 military airfields in Northern Ireland, most of which were constructed during the war. Their uses were many: Coastal Command landplanes for patrol duties and operational training; bases for carrier borne aircraft forming up and deploying to ships; more training was undertaken by large numbers of USAAF and RAF aircraft and personnel.

Many trainee pilots and navigators got lost and were unable to find their home stations. To assist them at Portaferry the duty crew would switch on a large searchlight, point it at a given compass bearing, and raise and lower the beam at regular intervals. Other searchlights in the Province were doing the same thing, all guiding the aircraft home. This system was apparently only used in Northern Ireland, given that it was relatively free of enemy intruder aircraft.

Many aircraft of all types were delivered to or dispatched from maintenance, modification and repair. Factory fresh aeroplanes were fitted out with equipment and sent to the front line or stored at readiness. These came from across the Atlantic and over from Great Britain. Two examples may be highlighted, Langford Lodge on the shores of Lough Neagh, became one of four primary air depots for the USAAF in the UK, where thousands of American bomber, transport and fighter aircraft were modified for active service. In its heyday, in 1943-44, some 7,500 people were employed there at the 3rd Base Air Depot - comprising about 1,500 military personnel, about 3,000 Lockheed staff and a similar number of local civilians, paid for from Lockheed funds. A truly staggering total of 3,250 new aircraft were assembled there, more than 11,000 were serviced and 450,000 components were overhauled. At nearby Nutts Corner, one of four Transatlantic Ferry Terminals in the UK, USAAF aircraft arrivals were recorded in gradually increasing numbers from July 1943; July 1944 was Nutts Corner’s record-breaking month when 372 twin and four-engine aircraft arrived from across the ‘pond’. To these may be added the aircraft constructed by Short & Harland, mainly Stirling heavy bombers and Sunderlands.

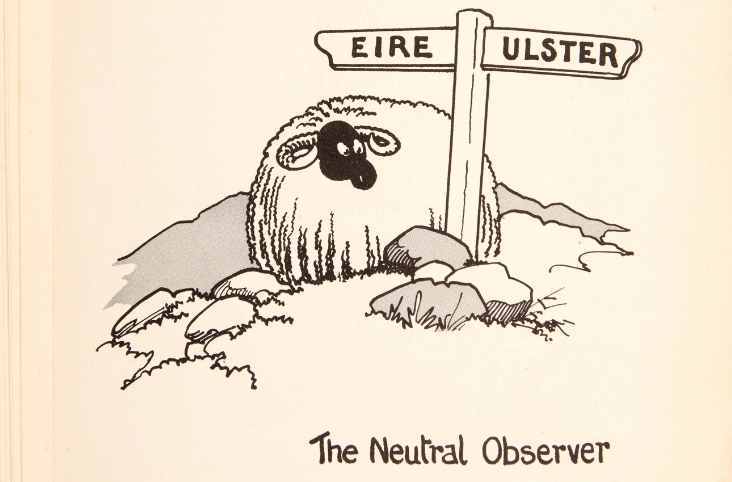

Some explanation should also be given of an aviation aspect of the co-operation with the Irish government which had to be seen not to breach Irish neutrality. An agreement was negotiated early in 1941 which allowed flying boats based on Lower Lough Erne to fly westwards to the Atlantic along an air corridor over Ballyshannon in Éire between Lough Erne and Donegal Bay. This served to increase the effectiveness of operations by reducing transit times and increasing the range of cover that could be given to convoys in the Eastern Atlantic. Land-based aircraft operating to and from other airfields also made effective use of the Air Corridor, within which, in Northern Ireland, the Americans operated a Radio Range that was constructed just to the east of Belleek as a navigational aid for aircraft being ferried from the USA as well as RAF Coastal Command aircraft returning to Lough Erne from operations over the Atlantic. Ongoing research will reveal more of this ‘hidden history.’

General Eisenhower was referring land, sea and air services when he declared, ‘Without Northern Ireland I do not know how the American Forces could have concentrated to begin the invasion of Europe.’ The airfields constituted the United Kingdom’s ‘unsinkable aircraft carrier’ and were vital to the war effort both with regard to preparing aircraft and crews for the invasion of Europe and winning the Battle of the Atlantic. Adequate support and ASR provision was accordingly essential.

Post war the RAF Marine Branch (as it was renamed in 1947) would continue with its unheralded work in our loughs and around our shores but these are other stories which deserve to be told inn due course.

About the Author

Guy Warner has written more than 30 publications on aviation, military and naval history as well as several hundred articles for magazines across the world.