Blog

Still Over Here Part 1: The archaeology of the United States military in Northern Ireland, 1941-45

The outbreak of war in September 1939 plunged Europe into what would become the most devastating and costly conflict in human history. German's invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 was met with an ultimatum from the United Kingdom (UK) and France to withdraw from Poland, but Hitler ignored this. Consequently, the UK and France declared war on Germany on 3 September. Poland fell in just over a month, and the campaign in Norway from April - June 1940 ended in defeat for the Allies. Nothing appeared to be able to slow the advance of Nazi Germany. After a lightning campaign in the west, Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands and France all capitulated to the German onslaught in the summer of 1940. The United Kingdom, supported by its overseas dominions, remained protected by the English Channel for the time being.

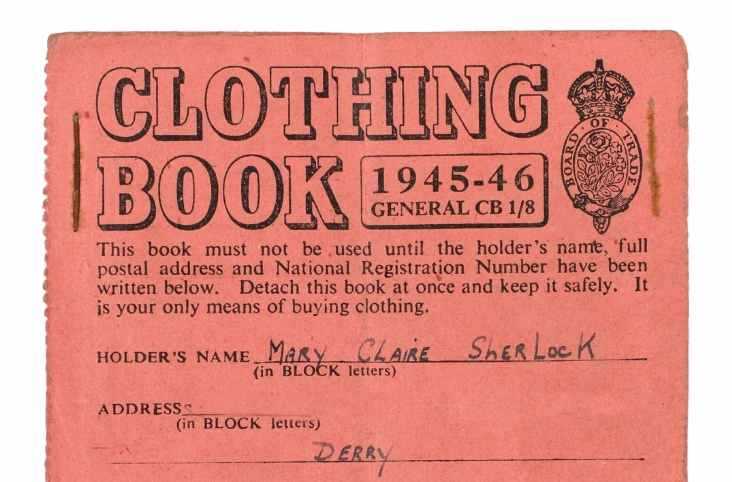

Many in the United States of America (US) hoped their country would stay out of the war and remain neutral. Yet, President Franklin D. Roosevelt instituted programmes to support the UK. In September 1940 came the Destroyers for Bases Agreement, through which the US Navy (USN) transferred 50 mothballed destroyers to the Royal Navy (RN) in exchange for land in UK territories on which the US would erect naval and air bases. In December 1940, Roosevelt made his 'Arsenal of Democracy' speech committing the US to arm and support the UK and Canada in their war against Germany. The Lend-Lease Act was signed on 11 March 1941, providing the UK and its allies with food, fuel and material in return for leases on military bases, which effectively ended US neutrality. The US massively expanded its military forces during this period, though many still wished for the US to avoid direct involvement in the war. However, this became a moot point with the Japanese attack on the US Pacific fleet anchored at Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1942. Four days later, Germany declared war on the US.

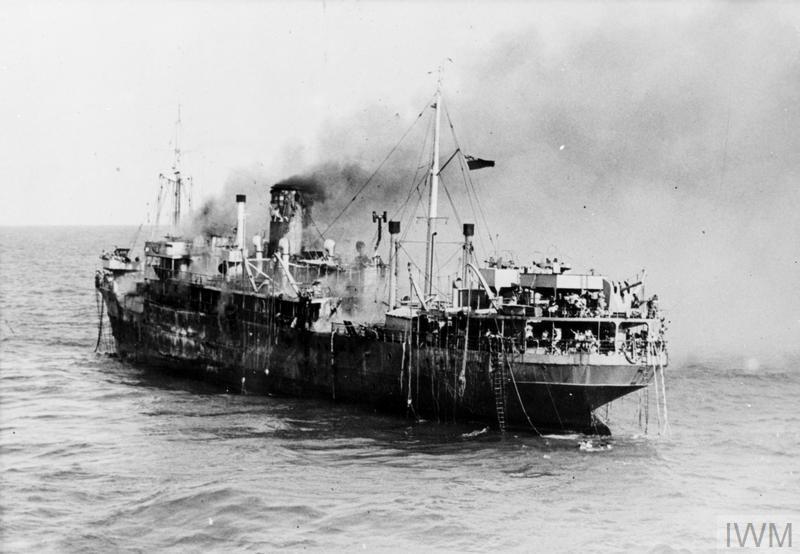

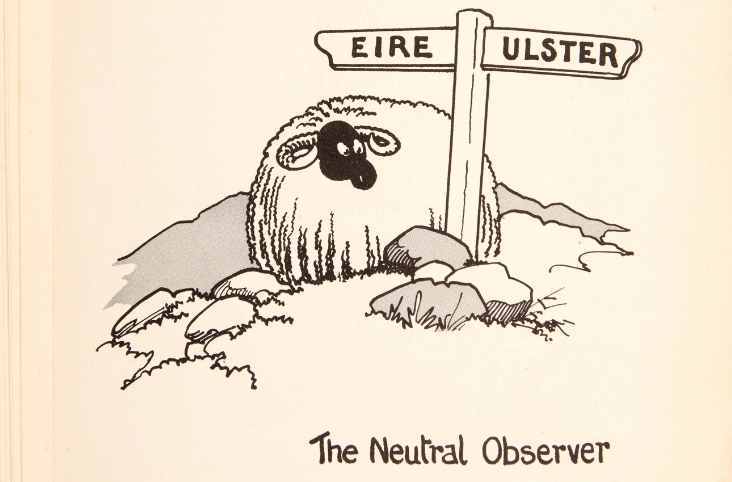

The fall of France in 1940 gave Germany access to the Atlantic ports along the French coast, forcing Allied convoys to take the more northern approaches to the UK. The UK expected to have access to the so-called Treaty Ports at Lough Swilly, Co. Donegal, Spike Island, Cork and Berehaven, Co. Cork. The refusal of the Republic of Ireland (officially known as Éire at the time) to allow Britain to use the treaty port at Lough Swilly made Derry/Londonderry crucial for the protection of the vital shipments of food, fuel, arms, equipment and later troops, across the Atlantic.

Though the US officially entered the war at the end of 1941, they prepared for their ultimate involvement in the war much earlier that year, in various places. One of these locations was Lisahally on the River Foyle. Shipments of men, materials, and equipment were sent to begin the construction of US naval facilities on the River Foyle. This became known as US Naval Operating Base 1. Work started on the base in June 1941, as 362 US technicians (also 25 USN Civil Engineer Corps officers in civilian clothes) and building materials arrived on the Foyle. Their number steadily rose over the coming months. A hutted camp was constructed at Beech Hill House, and piling began in October for a 300-metre wharf at Lisahally. When the US entered the war, the Americans at Derry/Londonderry had completed a radio station, the wharf, the naval repair base and the ammunition storage depot.

The USN further expanded the site by constructing repair shops, a hospital at Creevagh, communication stations, warehousing, and barracks with a capacity to house 6,000 personnel. A 300,000-barrel fuel tank farm was established, with associated pumping stations and fuel pipelines. A USN/RN combined operations room was built as part of a command-and-control facility on the grounds of Magee College. Heavily fortified reinforced concrete shelters protected the combined USN/RN HQ.

Much of the naval base has been removed or redeveloped, but some traces remain. The largest is the wharf built in 1941. It survives but is currently in a dilapidated condition. Two main sections remain intact, one 50m, the other approximately 100m long.

The US Army arrives:

When Private Millburn Henke of the 34th Infantry Division stepped off the Chateau Thierry, on 24 January 1942, he officially became the first serviceman to set foot in Northern Ireland. Thousand more soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines would follow him; approximately 300,000 more. The influx of US soldiers principally came in two waves. First, in 1942 the 34th Infantry Division and 1st Armoured Division arrived and were based around Northern Ireland. However, they had left by the end of the year to take part in the US amphibious landings in North Africa as part of Operation TORCH.

The second wave came at the end of 1943 when troops from the 2nd, 5th, and 8th Infantry Divisions and the 82nd Airborne Division were stationed throughout Northern Ireland to train in preparation for the invasion of Europe. GIs were stationed at many barrack sites across Northern Ireland, often within large walled demesnes such as Killymoon or Ballyedmond. Today these are one of the least recognised features of the US presence in NI, as often little remains apart from concrete hut bases of Quonset or Nissen huts. Though the camps are long gone, the graffiti left by the soldiers remains. Traces include carved names and service numbers cut into a tree or written in wet concrete. Others are quite artistic, as with this unit emblem of the 654th tank destroyer battalion, which remains in the Argory (Co. Armagh). The names and service numbers provide a direct link to real people facing an uncertain future as they prepared for war. One was Private Tony J. Vickery of the 505th Parachute Infantry regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, who left his mark in the basement of Killymoon Castle. Sadly, he was killed in action five days after parachuting into Normandy as part of the D-Day landings.

Training sites/ ranges:

Stationing thousands of US Army service personnel in Northern Ireland had one critical mission; to train them for service elsewhere. In combat units, this involved drills, route marches, and military exercises where they honed their skills in attack, defence, anti-aircraft gunnery and combat engineering and every other speciality needed to produce an effective fighting force. Over 80 firing ranges were established in Northern Ireland, which included artillery, mortar, anti-tank, field firing ranges and battle schools. Traces of these ranges remain visible in the landscape. The Dunseverick (Co Antrim) anti-tank range still retains its sturdy range blockhouses and what looks like a short runway. These structures enabled a target dolly to be towed along the range, simulating a moving target for the trainee anti-tank gunners. There are also smaller ranges for small arms training, as at Fecarry near Omagh (Co. Tyrone). The target shed and gallery along which the targets were placed remain in good condition, as does the stout concrete wall and earth bank, which protected the range crews from stray shots. A steel target lies in a nearby fence, and the environmental effect of firing thousands of rounds is evident. On the face of the hill beyond the range, very little grows as the ground is so heavily contaminated by the lead and copper jackets of the bullets fired over 70 years ago.

In parallel with the massive build-up of troops, facilities were constructed to store the many tons of explosives and ammunition required for operational and training purposes. Magazines could not be sited close to bases, barracks, or any population centres. Therefore, the US Navy established a munitions storage depot at Fincarn Glen (Co. Derry/Londonderry). The depot was completed in January 1942, and was composed of 21 steel storage bunkers cut into the side of the glen, which protected the magazines from air attack, and mitigated the effects of any accidental detonation. They were primarily used to store naval ordnance, three and five-inch shells, and torpedo warheads. However, small arms ammunition was also held there. The robust munition storage structures remain, though some are heavily overgrown. Moreover, traces of the men who worked there live on in the doodles and graffiti which can be found inside a number of the storage bunkers.

In part two, we will look at the traces of the US Army Airforce, which occupied six bases across Northern Ireland.