Blog

"The Bravest Man never to have been awarded the VC": A re-examination

On 9 April 1945, two squadrons of 1 Special Air Service (SAS) Regiment advancing outside Oldenburg, Lower-Saxony, were ambushed by a unit of German paratroopers, known as fallschirmjäger. Upon hearing that the unit's leading officer was among the first fatalities, the regiment's commanding officer and co-founder, Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Blair "Paddy" Mayne of Newtownards, Co. Down, careered to the scene despite strict orders not to lead missions in the field. His prompt assessment of the scene revealed that the source of the intense enemy fire was a group of farm buildings next to a densely wooded area. It is recorded that Mayne cleared the occupied farmhouses with single-handed, repeated bursts from his Bren machine gun before turning his sights to the woods. Having ordered a jeep forward and asked for a volunteer gunner, he started for the road alongside his pinned-down comrades. Lieutenant John Scott - volunteer - later provided an account of Mayne's following actions:

He drove up the road past the position where the squadron commander had been killed a few minutes previously, giving me cool precise fire orders… We stopped, turned the jeep around and drove back again into cover… Colonel Mayne fully realised the risk [of extricating the survivors], yet once more turned the jeep round and drove up the road… He jumped out of the jeep giving me orders to continue firing, lifted the wounded out of the ditch, placed them in the jeep and drove back to the main party. The enemy had by now been mainly killed or wounded, the few who remained were in full retreat.

In displaying an “unsurpassed gallantry”, he not only saved the lives of the wounded, but also broke “the crust of the enemy defences on the whole of this sector”, for which he was recommended the highest British military award for bravery: the Victoria Cross (VC). Controversially, however, this accolade was withdrawn anonymously six months later before it could be awarded.

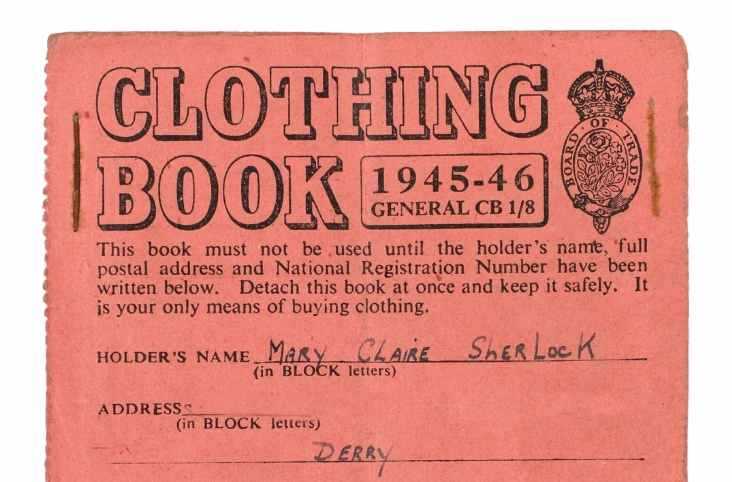

The explanation for the decision - and by those responsible - is still hotly debated. More contentious is the refusal since his premature death in 1955 to posthumously honour him with the award that King George VI remarked "so strangely eluded him". To this end, over 100 Westminster MPs signed three parliamentary motions in 2005 calling for a retrospective award: again, to no avail. We might, therefore, consider that Mayne's actions at Oldenburg weren't deserving of this honour. In any case, the Ministry of Defence is reported to have received more than one thousand such requests for countless gallant soldiers who have fallen victim to oversight, so why should Mayne's case be regarded in a different light?

Considering that his VC recommendation was signed off by no less than a brigadier, three generals, and Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, before its anonymous downgrading reveals the distinctiveness of this case. SAS founder David Stirling described it as a “monstrous injustice” while fellow SAS Original Jim Almonds commented; “Why he never got the VC, I don’t know. He earned it more than once… One of the most decorated men in the army: DSO, [three] bars, Légion d’Honneur. His face didn’t fit, but his actions did.” The approval – and frustration – of these notable figures forms the basis for the argument that the anonymous decision to downgrade Mayne’s award was discriminatory, particularly considering that the French government saw fit to award him their equivalent of the VC.

The contemporary depiction of a psychotic killer prone to blind, drunken rages will undoubtedly have upset the campaign for a posthumous award. The most commonly accepted myth on which Mayne’s detractors founded their criticisms concern his recruitment into the SAS. Three years after his death, American journalist Virginia Cowles published a biography on David Stirling; the origin of the fiction that he recruited Mayne from a prison cell in Cairo, Egypt, after the latter knocked his commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Geoffrey Keyes VC, unconscious. By 2016, this fiction had developed into a version in which Mayne, according to Ben Macintyre, struck Keyes before chasing his comrades at bayonet point in reaction to hearing that he had not been selected to take part in the daring raid to capture Hitler’s favourite General, Erwin Rommel. That Keyes led and ultimately died in the failed raid, did not bode well for Mayne's reputation, having allegedly struck a national hero who had since received a posthumous VC.

A closer glance at the contemporary documentation, however, reveals this to be a fabrication. Keyes disclosed in his diary that he was not present on the date that he is alleged to have been assaulted by Mayne but was at a dinner party outside of the city. The fiction then reads that Keyes was left with no choice but to kick Mayne out of the unit, despite the existence of a document written by Keyes himself detailing that Mayne simply “left the unit” after applying to be transferred to the Far East.

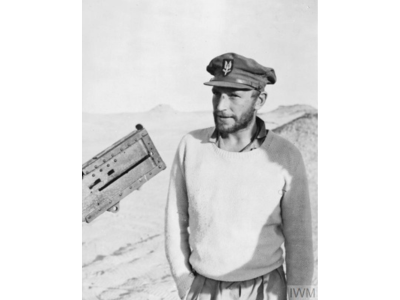

Furthermore, Stirling could not have visited Mayne in prison. Crucially, the suggested date of this visit in late June was only one week after Stirling’s disastrous first parachute jump in the desert which rendered him temporarily “paralysed from the waist down.” So too, coincidentally, was Mayne medically incapacitated. Later, Nursing Sister Jane Kenny wrote a letter to Mayne’s sister informing her that “He was a patient of mine last June, had a mild attack of malaria – much to his disgust.” Therefore, Mayne could not have been in prison, nor could Stirling have visited him on the suggested date.

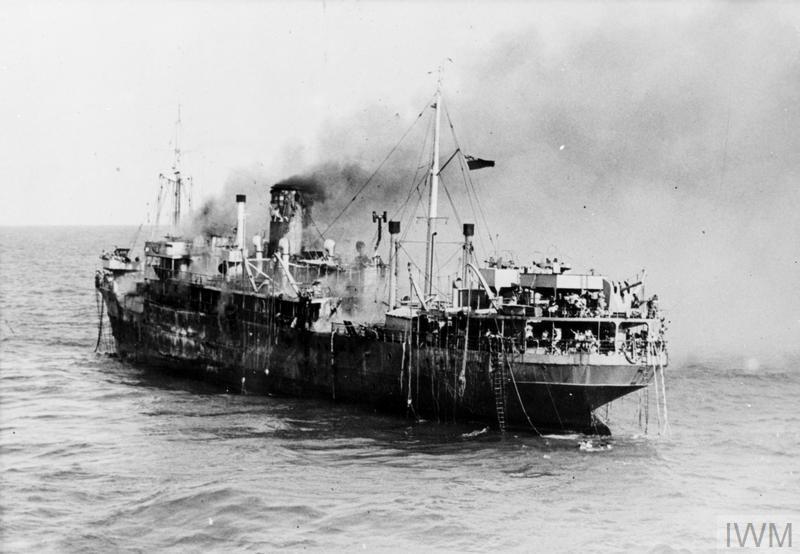

A further distortion of history for which Mayne is most popularly renowned surrounds the first successful raid in North Africa by the SAS. The attack on Tamet airfield, Libya, in December 1941 ostensibly cements the argument by Mayne’s detractors that he often acted with a mindless furore and can only have escaped each time due to unadulterated luck. Mayne led a cohort of SAS men onto the airfield overnight, with the objective of destroying as many grounded enemy planes as possible. Similarly, the fiction tells us that he spotted the lights under the door of a German-Italian pilot mess hut, kicked the door open and, in a cold-blooded and callous act, gunned down its 30 occupants.

Again, a study of the relevant documentation demonstrates that this does not add up. First-hand accounts confirmed that Mayne was armed solely with his favourite Colt .45 pistol and with it, shot the first pilot to move after a brief standoff, then the pilot closest to him, before setting off to finish laying explosives on the planes. The accepted version of this tale today, however, omits the fact that Mayne was flanked in the doorway by two comrades bearing Thompson sub-machine guns: fully automatic weapons capable of dealing much more damage than a sidearm. Not even Paddy Mayne could have reloaded his sidearm three times to shoot 30 panicked soldiers!

Numerous similar raids were carried out behind enemy lines and, as one historian observed, “There was no moral opprobrium attached to [these attacks] by High Command.” This inaccuracy is often the basis for singling out Mayne’s actions for reproach, little heeding the fact that he personally destroyed 40 planes that night and, by the end of the desert campaign, more planes on the ground than the RAF did in the air. His team’s tally at Tamet secured the future of the SAS within the British Army: a future which until that night had seemed all-but-nullified. “So,” recounted Stirling, “everybody now was quite happy that the unit wasn’t going to fold, because with a haul like that, they’d be stupid to say no more.” This also exposes the frailty of the argument that Mayne survived each raid through mere luck. He later wrote himself: “People think I’m a big, mad Irishman, but I’m not. I calculate the risks for and against and then I have a go.” Crucially, Stirling led a lesser-known, yet all-too-similar raid six months later, at Benina airfield while accompanied by Randolph Churchill, Winston’s son. After planting their timed explosives and preparing to flee, Stirling spotted a gleaming light under a hut door and decided to give the Germans “something to remember [them] by.” Randolph recorded Stirling’s actions next:

Inside, facing him, was a German officer seated at a table with about 15 German soldiers drawn up in front of him. David opened his hand and showed the Hun officer a hand grenade. The Hun wailed 'No-no-no!' 'Yes-yes-yes!' replied David, lobbing it in and closing the door!

Finally, until now we looked at modern-day portrayals of Mayne, but by learning how he was remembered by those with whom he fought alongside we gain a clearer insight into his more sensitive personality. Regimental Padre Fraser McLuskey recalled that Mayne “cared deeply and passionately for the welfare of his men…Paddy was the embodiment, on a large scale, of initiative, courage, daring, determination but at the same time he was sensitive and shy.”

SAS comrade John Randall supported this: “He expected people to work hard at being good soldiers and expected them to behave as gentlemen because he was one… He led from the front and people admired him… he would never ever commit to an operation that he wouldn’t be prepared to undertake himself.” Moreover, for a man nowadays described as “borderline psychotic” and “capable of cold-blooded killing”, it is perhaps surprising to learn of Mayne’s compassion regarding enemy prisoners. Before surrendering, he strictly instructed, “[enemies] must be subject to every known trick, stratagem and explosive which will kill, threaten, frighten, and unsettle them; but they must know they will be safe and unharmed if they surrender.” These instructions were to be “implicitly obeyed.”

Blair Mayne’s family recalled him rarely speaking of his wartime experience. As a result, his detractors faced little resistance in their efforts to tarnish the same reputation that garnered a mile-long funeral procession. The sources that would dispel their fabrications are at our disposal but have too frequently been dismissed by prominent historians. In the meantime, the sentiment shared by many – including the owner of the world’s largest VC collection, Lord Ashcroft – is that Blair Mayne may, to quote local historian Peter Forbes, “go down in history as the bravest man never to have been awarded the VC.”