As early as April 1941, the decision was taken to commence immediate construction of American bases in the United Kingdom.

Four sites were selected; two in Scotland and two in Northern Ireland. A seaplane station was earmarked for Lough Erne, and US Navy (USN) escort base was to use the existing Royal Navy facilities on Lough Foyle and Londonderry. This required construction of new facilities to include a wharf at Lisahally, a large machine shop, ammunition depot and any additional buildings as required.

In preparation for their construction, the US Navy department assembled the necessary material and equipment at Quonset Point, Rhode Island, for shipping to Londonderry and the Clyde.

Under the Lend Lease Act, the actual construction was outsourced to two civilian construction companies, Merriot Chapman Scott and George A. Fuller Company, under contract NO7-4850. However, their employees were supervised by US Naval personnel with Commander Bragg in charge.

For this workforce, the British Treasury, knowing that there was insufficient workforce in the UK to complete the required construction projects, agreed to pay an immediate deposit of six million dollars. Yet despite attempts by US authorities to lessen wage expectations to British levels, the American technicians were paid about 5 times more than their British equivalents.

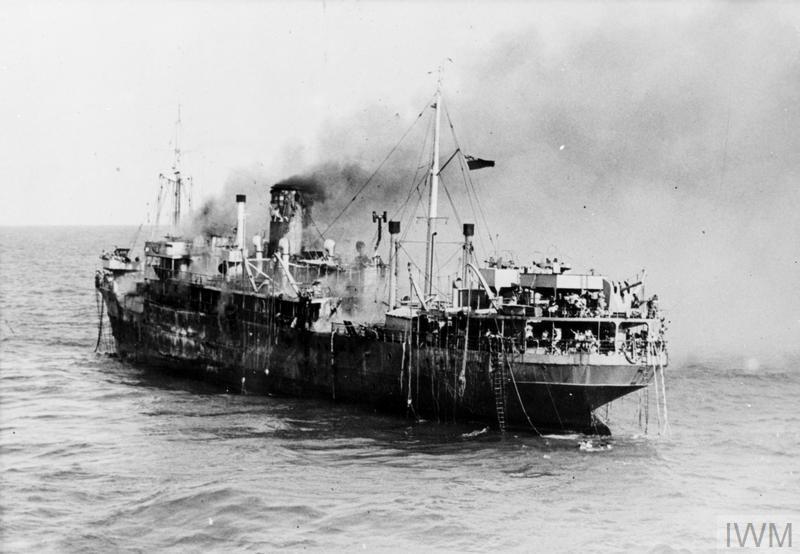

The first contingent of key men was due to sail from New York on 16 June, but they protested at their accommodation, feeding arrangements and the movement restrictions imposed on board their ship, the Indrapoera, whose captain then refused to sail. The men eventually sailed on board a British ship, the Pasteur which was deemed to have more suitable to their needs.

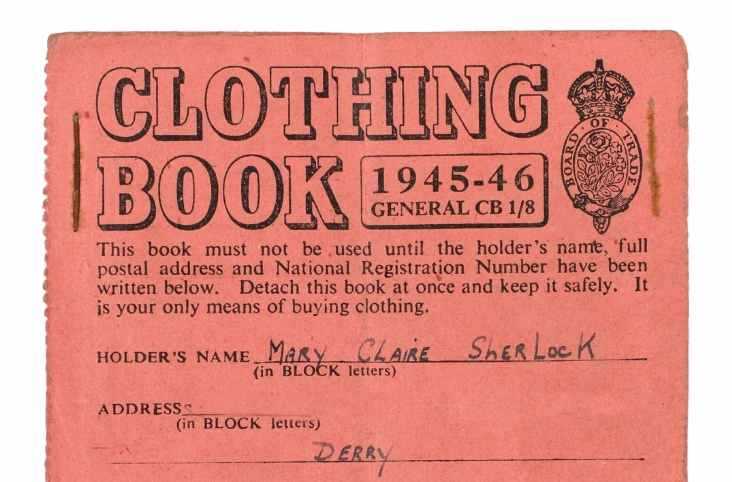

With the Pasteur expected to dock in Glasgow on 30 June and the men to be ferried directly to Londonderry, the issue of how they were to be registered upon their arrival in Northern Ireland was raised, as the men would technically qualify as ‘Aliens’ living and working within Northern Ireland for the British Government. The US Government however requested that the usual restrictions for ‘Aliens’ not be imposed on their citizens and so the idea of a special identity card, issued by the RUC - was suggested. Despite an initial order of 250 copies, later raised to 1,500, by early July, the technicians were eventually registered as ‘Aliens’, but their certificates were stamped to show that the holder was exempt from terms of the Aliens (Movement Restriction) Order, and if necessary from the terms of the Aliens (Protected Areas) Order.

Prior to the first sailing in June, a memo entitled ‘Publicity Arrangements concerning Employment of American Labour in the U.K' was circulated between the relevant authorities and it made clear that:

‘the arrival in the U.K. of contractors and labourers for the construction of bases should be treated as normal aid by the U.S.A... The men will be employed by the British Government and paid from British Funds…U.S. Citizens have, of course, a perfect right legally to accept such employment.'

It continued to request that:

‘American observers should take steps to ensure that it is explained to the contractors and labourers on arrival that they must regard themselves as being in British employ and pay, and that there is no necessity to hide this fact from the civil population’.

Unsurprisingly, the arrival of hundreds of Americans in Londonderry made the headlines, with the Belfast Telegraph describing them under the headline, 'The Technicians Who Won’t Talk' as 'a colourful lot, their yellow jerkins, multi-coloured shirts, and green corduroy trousers attracting much attention’

In the article the reporter expressed frustration, that despite repeated questioning, the clearly well-briefed Americans gave very little away. It was also apparent that the press were as well briefed as the men themselves with reiterations in some form or another of the previous publicity memo - 'one thing is clear...the men are in no way under military control'.

As the summer of 1941 progressed the number of Americans in Northern Ireland gradually increased, and by the end of August there were about 500 in Derry alone. At this time, censorship intercepts on mail between the Derry based technicians and their families revealed criticisms of American organisation and rowdy behaviour, such as drunkenness. Commander Bragg assured the local authorities that the letters did not give a proper picture of the conditions under which his men worked, nor did they represent the men's feelings towards the locals. However, he did acknowledge the ‘obvious limitations over here where the Puritan atmosphere is so strong’ and that Sundays were ‘dead’ in Northern Ireland, and that this helped contribute to some breaches of the law which were dealt with by the courts.

A small number of the workforce were even sent home or redeployed to Scotland. For example, in late July, Commander Bragg requested priority transportation home of six employees 'considered objectionable for further employment' . Yet overall, he was satisfied with the men's behaviour, ‘taking into account the difficulties inherent in the influx of such a large body of ‘lively Americans into a foreign country’. A further 90 did return to the US as they reportedly found the Northern Irish climate too trying and the life too boring!

Similar sentiments were echoed by the Inspector-General of the RUC, Sir Charles Wickham in September:

‘what trouble did exist was due to a sudden change from a very comfortable home life to the discomfort of a miliary barrack in a strange country, to the idleness of the waiting period between disembarkation and being started on the job and to a small percentage of the men not being sufficiently steady for this type of employment’

Wickham believed that after another 60 men or so were repatriated, there would be no further trouble.

Issues of course persisted in isolated instances that included motor offences, malicious damage, being drunk and disorderly, assault and stealing. Nevertheless, long after their arrival the presence of the technicians continued to make the news in an overwhelmingly positive and sometimes curious manner.

One of the most remarkable stories involving the US technicians was the reunion of a father and son, who had lost contact five years previously, in the middle of the blackout in a Northern Irish town. They were reunited when 50-year-old Melvyn Oakes, who had volunteered to work in Northern Ireland, was knocked over by a bus carrying another party of Americans that coincidentally carried his son, Sheldon!

Some joined the local Ulster Home Guard Battalions, and a Pat Jefferson from San Antonio, Texas even joined the Apprentice Boys of Derry.

Another, Thomides Douglas, a naturalised Greek who served in the First World War and a superintendent amongst the technicians, became the godfather of the second child of Mr and Mrs Wright. There are also marriages recorded between local women and the technicians that pre-date the widely celebrated first GI Bride wedding in April 1942.

Even the Hollywood actor, Robert Montgomery, who was by August 1941 the U.S Naval Attaché in London, was based for a short time in Northern Ireland with duties related to the work of the technicians.

And finally, the head baker for the technicians, Michael Harold Murphy, found himself hospitalised in Musgrave Park Hospital in October 1941 for his 113th operation! Murphy had been gassed in France during the First World War when he fought as part of the American Expeditionary Force and had suffered from lung trouble ever since.

Tragically, a small number of the Americans died whilst in Northern Ireland. In September 1941, Dalmer E Martell, Boston and Robert Burgess, New York died of natural causes. The following month, Edmund J Casey, Pittsburg was fatally injured whilst working on the construction of an airfield north of Londonderry when the bulldozer which he was operating fell over the edge of a quarry. Casey was repatriated and was buried in Saint Bernard's Cemetery, Fitchburg, Worcester County, Massachusetts, USA on Feb. 4, 1942.

As 1941 drew to a close, the eventuality that the technicians had been preparing for occurred. The USA formally entered the Second World War after the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. Within the coming months the US technicians were soon be joined by their military compatriots and many requested to return to the US so that they could sign up to fight instead. For those that remained, the 'whole atmosphere' in which the Americans worked changed, taking on the speed and 'discipline of a wartime character'.

Before the official arrival of US forces however, the technicians unknowingly began what became a common theme for the American presence in Northern Ireland during the Second World War, and that was the throwing of a large Christmas party for local children as part of their many charitable efforts.

Over 7,000 school children from 22 schools in Londonderry were treated to a free cinema show, where they were greeted by Santa Claus and given a bag of candy. Similarly, patients young and old of the Londonderry City and County Hospital were described as enjoying the 'handsome' Christmas tree that was donated by the technicians.