Chris Ranstead

Wartime Bomb Disposal

As the UK was attacked by the Luftwaffe in the summer of 1940, the authorities quickly realised that unexploded bombs from these raids not only posed a threat to life well after the 'All Clear' had sounded, but they also disrupted transport and communications, in addition to severely hampering vital war work.

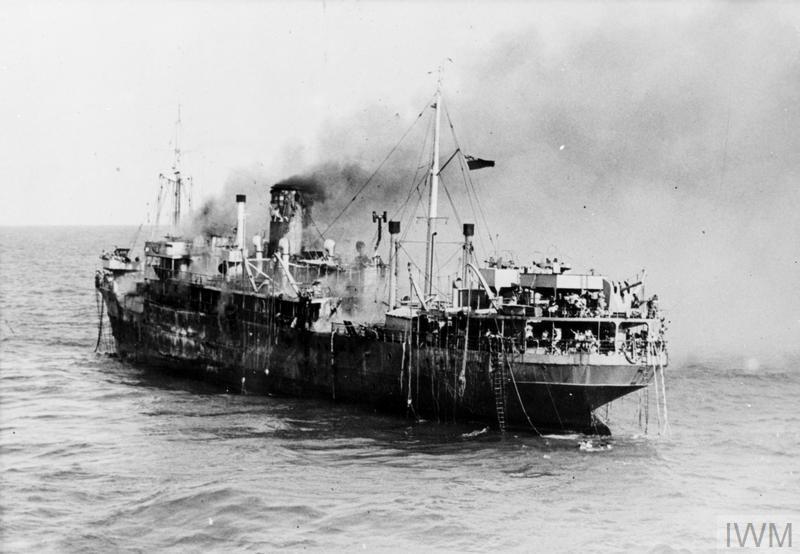

The Royal Engineers were tasked with clearing these unexploded bombs (UXBs). The RAF also dealt with numerous other bombs that had not gone off, on airfields and at aircraft crash sites. The Royal Navy too were involved, disarming UXBs in tidal areas, and unexploded nautical weapons, such as parachute mines. (The Germans realised their mines, designed for destroying ships also had a great blast effect against city streets). Though the different branches of the armed forces had different responsibilities, the reality was, that they all helped each other when necessary.

In March 1945 the Royal Engineers assisted the Navy in finding a British anti-submarine ‘hedgehog’ bomb that had somehow found its way to the bottom of Pollock Dock, Belfast.

With major UK cities bearing the brunt of the Blitz, Belfast was acknowledged as an obvious target, evidenced by four raids on the city in April and May 1941 that became known as the Belfast Blitz.

A Royal Engineers bomb disposal unit, 109 Section, had already been formed in June 1940, and wasbased at Kilroot Fort on the western coast of Belfast Lough. However, it was decided in Spring 1941, to amalgamate this section into the newly formed 27 Bomb Disposal Company. An advanced party from this Company arrived from England on the 4 May to bolster 109s resources. That very evening, and the evening that followed, the Luftwaffe returned to Belfast. The Bomb Disposal squad were immediately in the thick of it, rendering safe UXBs from these raids.

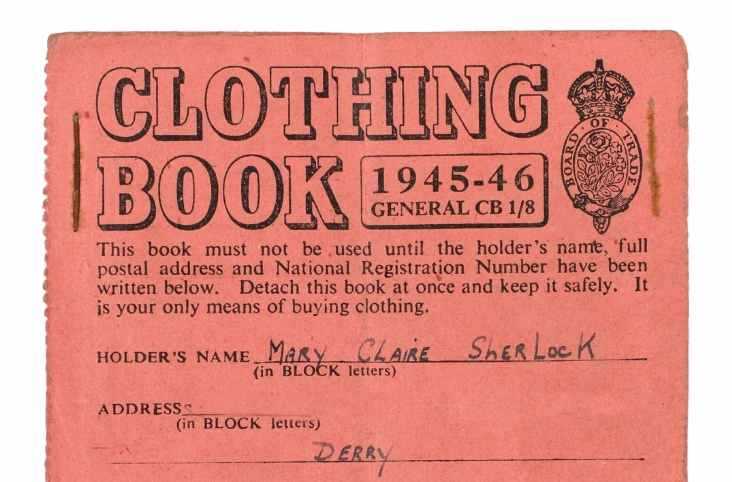

In all, 27 BD Company employed nine Sections in Northern Ireland during the war, numbered 20, 33, 35, 54, 71, 76, 109, 189 and 250. They were based at various locations, including billets in University Road, Belfast and Culmore Camp, Londonderry. Others were in camps at Templepatrick, Belmont, Donaghcloney, Carryduff, Newtownbreda, Boulderstone House, as well as Stormont Castle and the Massereene Arms Hotel in Antrim.

Based at Templepatrick Camp was No. 33 BD Section commanded by Lieutenant John Henry Havelock Gray.

He was later posted to Plymouth and awarded a George Medal for his bomb disposal work there.

Experienced bomb disposal officers were brought in to lead the units, including Major John Richard Filgate McCartney. He became the Commanding Officer of 27 BD Company. Born in Antrim, he had served in the First World War, coming back to serve again in the Second World War as a Bomb Disposal officer.

In January 1941, McCartney worked on a UXB on a farm at Hartshorne, Derbyshire that required his squad to dig in wet ground down to a depth of some twenty-eight feet. There was a constant risk of the shaft collapsing. It took a week to render the bomb safe and McCartney was awarded a George Medal for this action and a number of others.

Lieutenant Douglas Stanley Frederick Rayner was another veteran of the First World War, also posted to Northern Ireland.

In September 1940 Rayner, having been re-Commissioned as a Royal Engineers Bomb Disposal officer, defused six bombs that had dropped on an aircraft factory at Castle Bromwich, Staffordshire, resulting in only half a day’s production lost. A few days later at another factory in Birmingham he dealt with a 250Kg bomb with a damaged, (but still ticking!), ‘delayed action’ fuze, that could have detonated the bomb at any moment. It took him a nerve racking 35 minutes to prize the fuze out of the bomb with a marlin spike. He was subsequently awarded a George Medal for his efforts.

Rayner became the 2nd in Command of 27 BD Coy, in May 1943, based at Carryduff Camp.

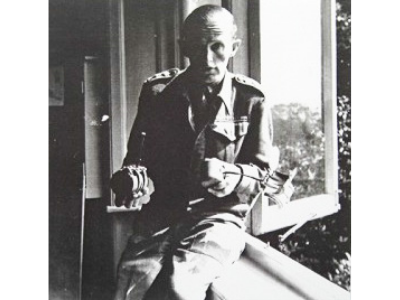

In March of 1944 Captain J.R. Griffiths, seen here holding German ‘butterfly’ bombs, was posted to 27 BD Coy as the new 2 I/C.

The Royal Navy also sent their experts to Belfast deal with unexploded mines. These mines were designed to fall in water, a parachute breaking their fall to protect their delicate mechanisms on impact. (The parachute was attached by a soluble link). These mines were fitted with a self-destruct mechanism that would blow them up should they fall in shallow water, or on land, thereby protecting the secrets of how they worked. This self-destruction would occur around 17 seconds after the mine struck, unless in the meantime the pressure of surrounding water over-rid the self-destruct switch. These mechanisms often failed, however, when the mine hit a hard surface, despite the parachute, (which was really meant for a water impact). The mine would then remain unexploded, but further disturbance, even the slightest vibration from a nearby vehicle, or a man attempting to defuse it, could re-start the self-destruct mechanism running down the final seconds to detonation.

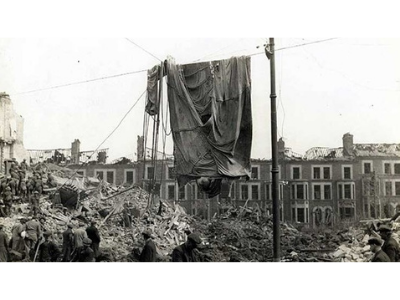

The parachute from a mine that struck the Antrim Road during the Easter Tuesday Raid. These mines were usually dropped in pairs.

One man sent to Belfast and deal with mines was Australian Geoffrey John ‘Jack’ Cliff.

He was part of a team that worked on a mine that had buried itself in about 14 feet of mud and water in the harbour in May 1942.

He worked on another a short time later that was in the Central Basin Reservoir. He was awarded the George Medal for his work on a number of mines around the UK.

Another of those that helped render safe parachute mines was Leading Seaman John M’Fetridge from Larne. He was awarded a George Medal for his help with particularly difficult mines in Cardiff and Birmingham. In August 1941 he was presented with his 15 year Good Conduct Long Service medal at the Regal Picture House, Larne, in front of the Mayor and other local dignitaries.

One of the larger bombs dropped was the 1800 Kg ‘Satan’, like this one that fell in Bangor.

One bomb recovered from Ashley Gardens, Belfast, had its filled in excavation subside after some rain, resulting in a driver damaging his car as he hit the depression in the road late one night in October 1941. But UXBs did not just effect the people. - The Veterinary Hospital at Edenmore House, once the home of Lord Shaftesbury in Shore Road, had to evacuate all their animals due to the presence of unexploded bombs in their grounds.

When there were no German bombs to be working on, the BD sections cleared ranges. These included Windy Hill on the Coleraine-Limavady road, Derrywarragh Island, Ballygawley, Slieve Croob, Daisy Hill Altahullion, Collinward, and at Hawthorne Hill, Killeavey. This was an important task, demonstrated by the fact that 11 year old Joseph Withers, was reported by the Belfast Telegraph in October 1941 as having been killed by an explosion near Aughnagurgan, after finding some unexploded bombs. A newspaper report in April 1942 also reported the death of 14 year old John Bogue, of Brookeborough, Co. Fermanagh, killed as he handled a bomb found near a military range. Another boy, Thomas Malloy Ferla, was killed in 1945 by a bomb on Corran Mountain, another area used for live firing practice.

In quiet periods personnel also helped in construction of PoW camps, defensive structures, anti-aircraft batteries and such like. They even assisted local farmers in summer months. However, as the war came to an end, the men of bomb disposal were still required to risk their lives dealing with the UXBs when found.

On the 25 October 1945, a 250Kg bomb containing delayed-action and anti-handling fuzes was uncovered at Belmont Road, Belfast. It was close to the Telephone Exchange serving the Northern Ireland Parliament. The anti-handling fuze was successfully dealt with, but it was found necessary to move the bomb away from the excavation for destruction with its delayed-action fuze still in place. A large electro-magnetic clock stopper was fitted to the bomb to prevent the fuze from operating. However, the clock stopper was damaged as an attempt was made to move the bomb. This made the task that much more dangerous. In spite of this, with great devotion to duty and regardless of personal safety, Captain Deacon and Sergeant Parker completed this most hazardous work, thereby removing the danger to the telephone exchange and enabling large numbers of people, who had been evacuated at short notice, to return to their home.

The telephone exchange bomb at the bottom the excavation prior to it being moved and destroyed.

Some bombs that fell earlier in the war, but their recovery abandoned due to water logged ground, etc, were re-investigated. A 250Kg bomb at Kerrs Farm, Gransha, Ballygrainey, that was abandoned in June 1941, was recovered and blown up in September 1945. Others investigated around Belfast were at Kensington Gardens (pictured below) and at the Ballymacarrett railway junction. One at Hollywood Road was found 18 feet down. It was removed to adjacent open ground and detonated in October 1945.

One wonders if there are any others still waiting to be found!

About the author:

Chris Ransted works for the National Archives in London as a Freedom of Information researcher. He is also the Archivist for the RAF Bomb Disposal Association, and has written numerous magazine articles relating to the subject, as well as the books ‘Bomb Disposal and the British Casualties of WW2’, Disarming Hitler’s V-Weapons’, and ‘Bomb Disposal in World War Two’.